We cover an array of topics here: click on the categories below to focus on your particular interest, or simply read them as we wrote them. We promise no linear narrative here.

case histories

case history: a year in bhutan /

case history: a year in bhutan

Invited to Bhutan to imagine a new retreat, we suddenly realize we have a lot to offer international projects. We have Dutch and American passports that allow us to travel almost everywhere, we have extensive and very diverse experience as architects and interior designers, we have powerful and completely portable software on our laptops that allows us to set up shop anywhere there's power, and we regularly tie into powerful tools and storage in the cloud whenever we have internet access. Plus, travel completely lights us up: intellectually, emotionally, spiritually. We were in Bhutan after a rather exhausting itinerary just 5 days after first getting the invitation to discuss the project.

In Bhutan, we were impressed first by the mist and the clouds. They imbued everything with a mysterious quality that suggested we were lucky for every gorgeous view we were afforded. This sense of mystery pervaded the entire trip.

We were of course fascinated by the uniformity and power of the architecture, especially the Dzongs and Lahkangs of some centuries ago but also the little chortans and alters encountered by the roadside.

Finally, we were confronted with a very specific jurisdictional mandate: respect this country's culture and architecture in designing this new retreat. It was difficult to understand exactly what that meant. Would there be any space for exploration or conversation? Would we simply be shoehorning new uses into old forms? Would the marriage between western sensibilities and expectations and Bhutanese culture be a one-sided union?

Surprisingly, not at all.

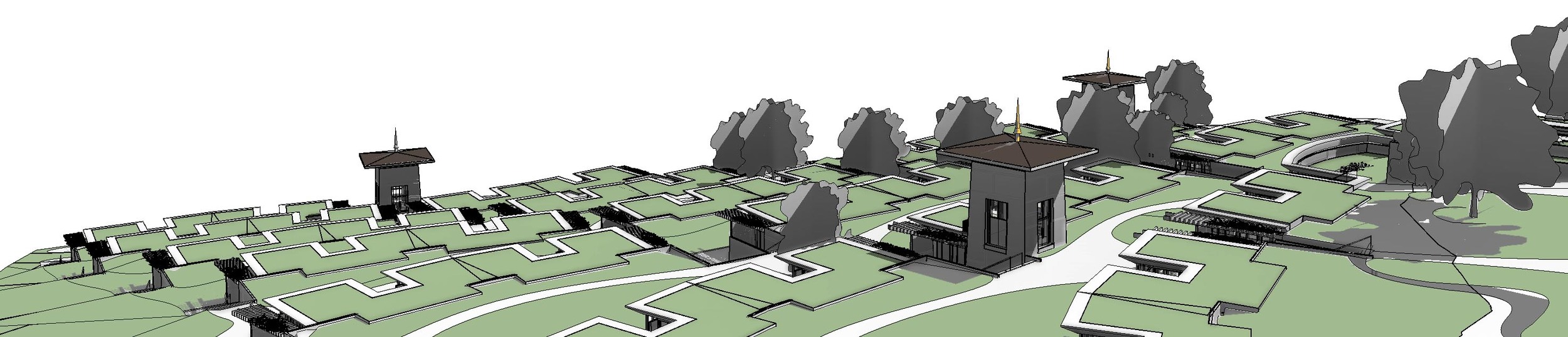

The site was misty and remote and insulated by a magnificent and protected blue pine forest.

It was damaged from grazing and once hosted a buckwheat field. When we scratched the surface of the terrain we encountered little surprises: a frog, water, abandoned implements.

We started from one simple idea, that this project should offer exactly what drew visitors to Bhutan in the first place: mystery and discovery, It should pique curiosity, and appeal to the adventurer. It should reward investigation with surprise and delight.

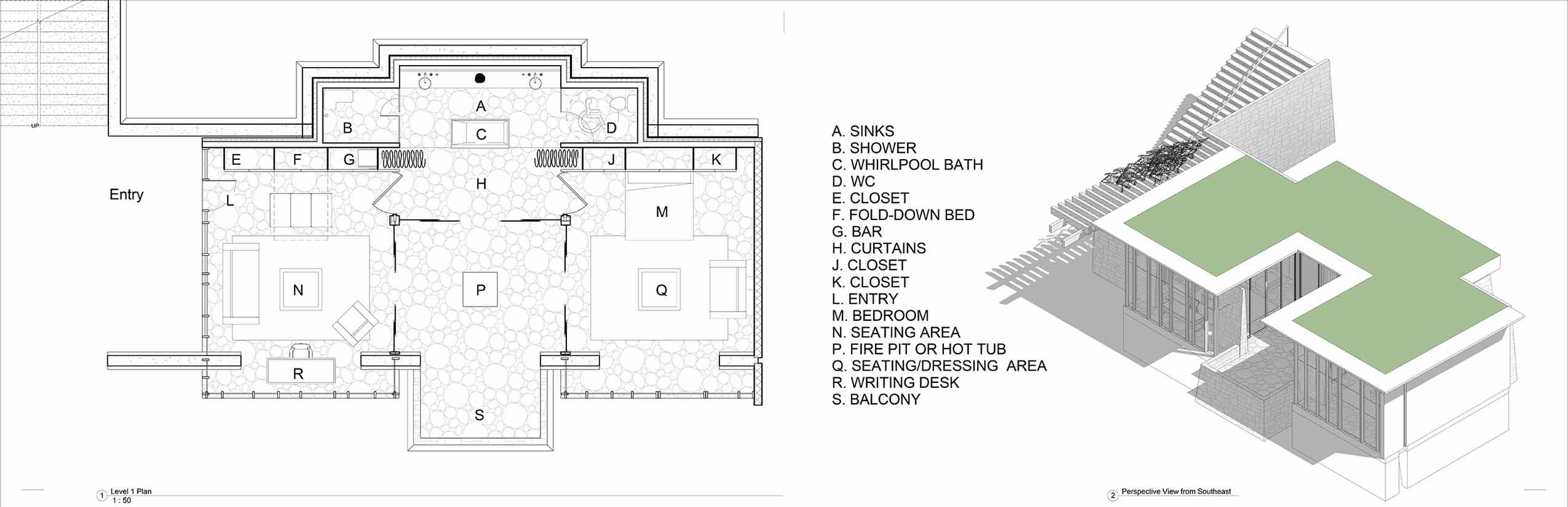

We brainstormed experiences that evoked these qualities, and they became points of reference. Lifting the cover of a new book. Opening a strange box. Walking along a curved wall. Stumbling on the unexpected. Entering a dark cave. Separating a Nesting Doll. Discovering something hidden. For example, in imagining the Villas that would hide in the trees we created a nesting doll, with a carved wooden enclosure inside a glass jewel box, and a stone chamber inside that wooden enclosure, and then not some dark dank cave of a chamber, but a beautifully sunlit room filled with glass jewels reflecting brightly so that the visitor experiences one kind of "enlightenment".

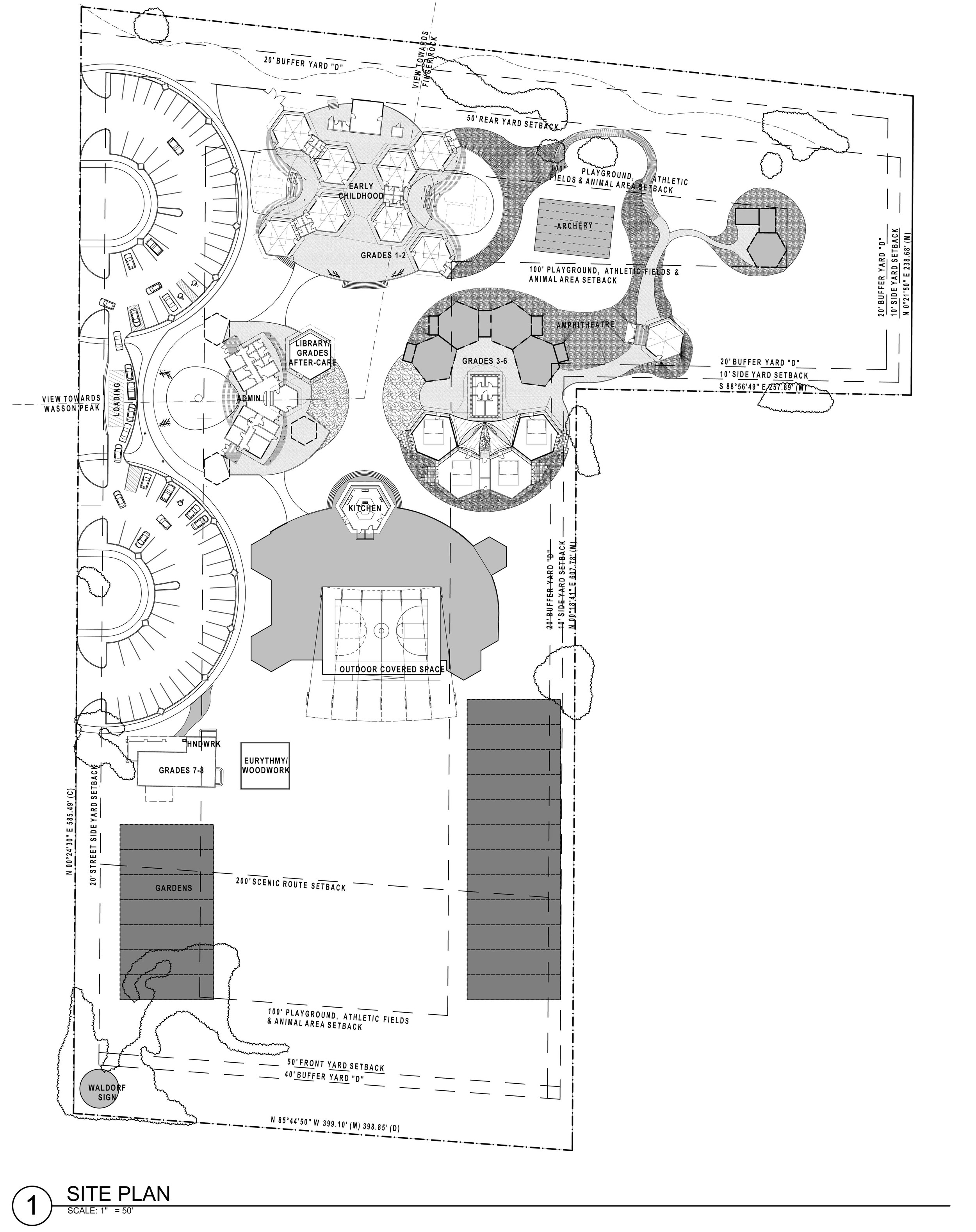

When it became clear that we would host a majority of the residences in the old buckwheat field, we thought to hide them under newly planted buckwheat in newly formed terraces, drawing our inspiration from the many rice paddies we had seen in the country.

We were warned that earth covered buildings would never earn Ministry approval, but we felt certain that it was appropriate here to build a garden and not a village. We felt too, that earth-covered dwellings would be a very useful tool in the jurisdictional planning toolbox.

Overlooking these terraces, the main building, the lodge, started as a series of narrow volumes creating courtyards between them, and ended up as a doughnut surrounding a single courtyard punctuated by a tower or "utze" housing cafe and private apartments.

We presented our first design to the Ministry of Works and Human Settlements in December, with mixed results. Earth-covered buildings and our intention to build a garden and not a village, preserving the original buckwheat field, was met with understanding and approval. Inverted roofs, elliptical shed roofs, and modern skylights were rejected.

We went back to the drawing board and completed our conceptual design a few months later.

Now we wait for project funding, hoping our design is powerful enough, persuasive enough, alluring enough to attract an investor.

case history: the desert home /

case history: the desert home

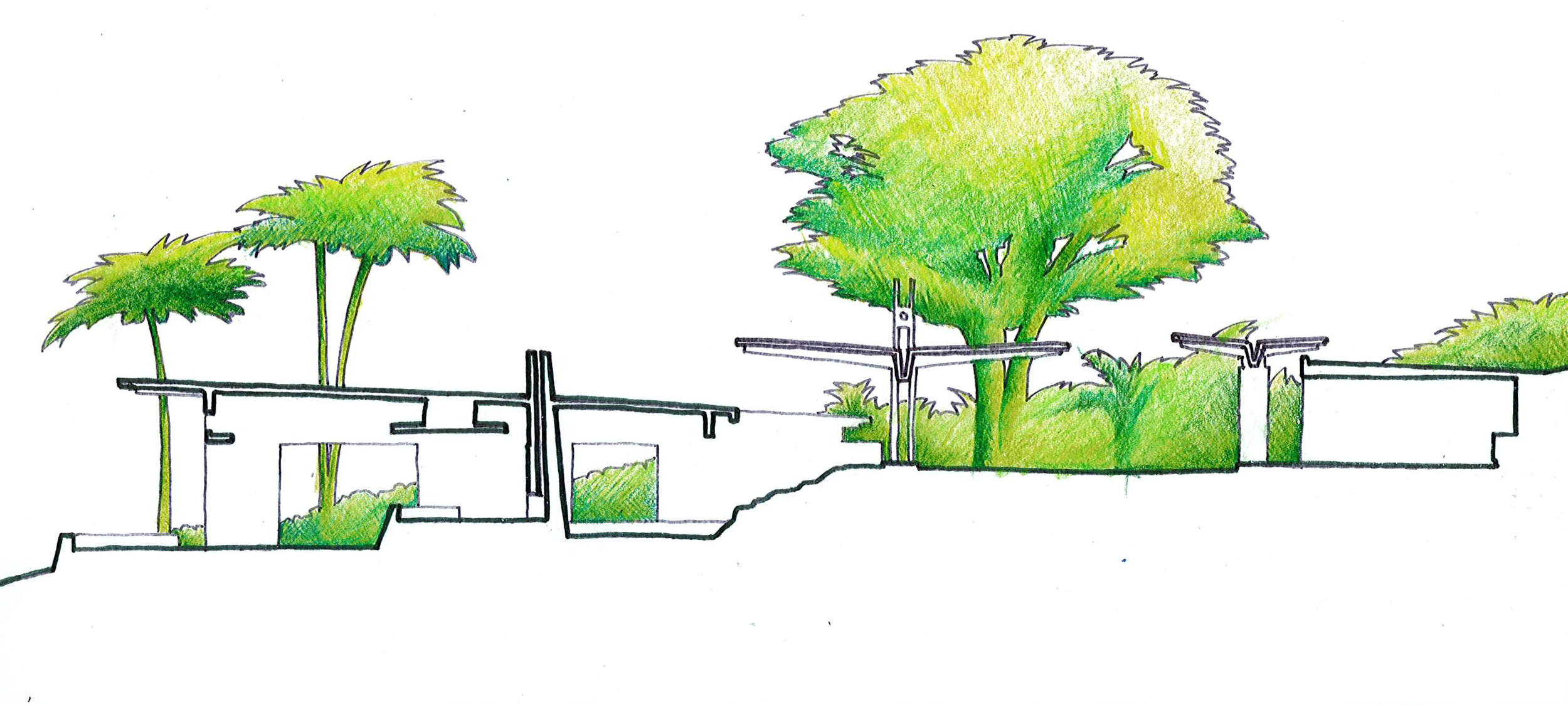

Our ideas about building in the desert come from three months spent crossing the Sahara Desert in 2006, and from 6 years now in the Sonoran Desert of Arizona. From the Sahara, we got a visceral sense of the difference between building with earth and building with concrete. The bottom line was this: In the absence especially of large quantities of expensive insulation, earthen construction was almost always comfortable, and concrete construction rarely so. In the Sonoran Desert, we've come to draw inspiration from the creatures that operate comfortably in the environment, and extract typologies from that examination. The house discussed here draws from the Desert Tortoise, relying on a tough, insulating shell to shield the more vulnerable living space within.

...a face only his mother could love...